Seowon culture of Joseon

Seowon: history and function

All sound files (아래 목록을 클릭하시면, 해당 부분의 음성파일을 들으실 수 있습니다.)

- World heritage

- UNESCO World Heritage List: Logo and Meaning

The history of seowon

Let’s now go back to the Joseon dynasty to see when and how the seowon was introduced to Korea.

The very first seowon was constructed in 1543, the 38th year of King Jungjong, by Ju Se-bung, the magistrate of Punggi-eup. Named “Baegundongseowon,” it was built on the site of the home of An Hyang, a local Confucian scholar. In 1550, the fifth year of King Myeongjong, Yi Hwang persuaded the king to change the seowon’s name to “Sosuseowon”—making it the first seowon to be named by a king. The new name was engraved onto a hyeonpan, a wooden board that featured the name of a building, and presented to the seowon.

Seowon named by the king, which were called “sa-aek seowon,” also received material support from the royal budget, including books, land, and slaves. The many seowon that were founded after Sosuseowon became a leading force of Joseon society, and it is around this time that the sarim emerged.

Sarim” refers to members of the literati class who focused on academic learning and the development of moral discipline. The job of the seowon was to cultivate well-trained sarim. In essence, the seowon was an incubator of the political and social activities of the sarim. The seowon of Joseon served not only as a shrine for honoring venerable individuals but also as an institution that played a large role in creating an educational and cultural environment for its local community.

During times of national crisis, seowon students (sometimes as many as 10,000) would write a joint petition, called sangso, to the king based on their sense of responsibility as intellectuals to help “set things right.” Starting in the 18th century, however, many seowon departed from their founding ideals, which resulted in various wrongdoings coming to light amid intense criticism. The collapse of the sarim simultaneously brought about the decline of the seowon. After the royal degree to close down all seowon was passed in 1871, only 47 seowon survived.

The seowon placed great value on people, philosophies, academic learning, and academic values. They taught students to live with honor as true literati who were faithful to their government and were willing to make sacrifices for their country, no matter how big, if necessary. The values of the seowon, which are evident in its buildings, natural surroundings, people, and moral and cultural systems, are unique and competitive enough to continue being passed down today. Efforts are being made to develop diverse and useful content related to Korea’s seowon, which will be available in the near future.

Korea’s seowon are now no longer “old houses” found only in history books. Amid the modern era’s emphasis on material value, the seowon is emerging as a means of creating a brighter, more hopeful future through its emphasis on moral fortitude.

The very first seowon was constructed in 1543, the 38th year of King Jungjong, by Ju Se-bung, the magistrate of Punggi-eup. Named “Baegundongseowon,” it was built on the site of the home of An Hyang, a local Confucian scholar. In 1550, the fifth year of King Myeongjong, Yi Hwang persuaded the king to change the seowon’s name to “Sosuseowon”—making it the first seowon to be named by a king. The new name was engraved onto a hyeonpan, a wooden board that featured the name of a building, and presented to the seowon.

Seowon named by the king, which were called “sa-aek seowon,” also received material support from the royal budget, including books, land, and slaves. The many seowon that were founded after Sosuseowon became a leading force of Joseon society, and it is around this time that the sarim emerged.

Sarim” refers to members of the literati class who focused on academic learning and the development of moral discipline. The job of the seowon was to cultivate well-trained sarim. In essence, the seowon was an incubator of the political and social activities of the sarim. The seowon of Joseon served not only as a shrine for honoring venerable individuals but also as an institution that played a large role in creating an educational and cultural environment for its local community.

During times of national crisis, seowon students (sometimes as many as 10,000) would write a joint petition, called sangso, to the king based on their sense of responsibility as intellectuals to help “set things right.” Starting in the 18th century, however, many seowon departed from their founding ideals, which resulted in various wrongdoings coming to light amid intense criticism. The collapse of the sarim simultaneously brought about the decline of the seowon. After the royal degree to close down all seowon was passed in 1871, only 47 seowon survived.

The seowon placed great value on people, philosophies, academic learning, and academic values. They taught students to live with honor as true literati who were faithful to their government and were willing to make sacrifices for their country, no matter how big, if necessary. The values of the seowon, which are evident in its buildings, natural surroundings, people, and moral and cultural systems, are unique and competitive enough to continue being passed down today. Efforts are being made to develop diverse and useful content related to Korea’s seowon, which will be available in the near future.

Korea’s seowon are now no longer “old houses” found only in history books. Amid the modern era’s emphasis on material value, the seowon is emerging as a means of creating a brighter, more hopeful future through its emphasis on moral fortitude.

Functions of the seowon

Throughout his political career, Yi Hwang emphasized the need for the seowon to be the “incubator” of intelligent individuals of merit to serve in the central government—an argument that befits the individual who made Sosuseowon the first royally sponsored seowon.

The traditional roles of the seowon, which was ideally regarded as the birthplace of capable civil servants, were: academic teaching, conducting rituals for deceased individuals of merit, and forging networks by enjoying one another’s company in nature.

The traditional roles of the seowon, which was ideally regarded as the birthplace of capable civil servants, were: academic teaching, conducting rituals for deceased individuals of merit, and forging networks by enjoying one another’s company in nature.

Veneration

The seowon devoted significant resources and care to the act of veneration, or honoring and passing down the learning of great scholars.

Korean seowon are characterized by their conducting of veneration only for local meritorious individuals and not Confucius, as was done by Seonggyungwan, hyanggyo, or state-operated provincial schools, and the traditional Confucian educational institutions of China and Japan.

The individuals honored at a seowon’s shrine are mostly those who have had a significant influence on Korean intellectual history. In other words, the status of a seowon was determined not by the size of its buildings but whose spiritual tablets were in its shrine building. Those who had outstanding academic accomplishments not only had many students but also many seowon throughout the country that honored them.

A seowon was typically built on a sloping lot without any other buildings in front of it. The front section was devoted to teaching, while the back—the highest part of the seowon—was occupied by the shrine, which housed the spiritual tablets of meritorious individuals. Veneration was conducted at the shrine.

Veneration was the act of visualizing the seowon’s commitment to preserving the philosophy of enshrined individuals as well as a time in which members of the sarim strengthened bonds with one another. There were three major rituals: Chunchuhyangsa, performed every spring and fall; Sakmangrye, performed on the first day and full moon of each month; and Jeongalrye, performed around the fifth day of each lunar month. Of these rituals, Chunchuhyangsa was considered the most important.

The rituals took two days to complete, including the preparation process that was done the day before. The preparations usually involved preparing the foods and utensils to be used, deciding who the officiants will be, and writing the chukmun, or a document read at the beginning of a ritual to call upon the spirits of the enshrined persons. On the second day, the participants would wake up at dawn to prepare physical and mentally for the ritual. After everyone dressed in the required attire, they would gather at the shrine. The officiants would then conduct each step of the ritual as written on a document called “holgi,” which was read aloud.

Korean seowon are characterized by their conducting of veneration only for local meritorious individuals and not Confucius, as was done by Seonggyungwan, hyanggyo, or state-operated provincial schools, and the traditional Confucian educational institutions of China and Japan.

The individuals honored at a seowon’s shrine are mostly those who have had a significant influence on Korean intellectual history. In other words, the status of a seowon was determined not by the size of its buildings but whose spiritual tablets were in its shrine building. Those who had outstanding academic accomplishments not only had many students but also many seowon throughout the country that honored them.

A seowon was typically built on a sloping lot without any other buildings in front of it. The front section was devoted to teaching, while the back—the highest part of the seowon—was occupied by the shrine, which housed the spiritual tablets of meritorious individuals. Veneration was conducted at the shrine.

Veneration was the act of visualizing the seowon’s commitment to preserving the philosophy of enshrined individuals as well as a time in which members of the sarim strengthened bonds with one another. There were three major rituals: Chunchuhyangsa, performed every spring and fall; Sakmangrye, performed on the first day and full moon of each month; and Jeongalrye, performed around the fifth day of each lunar month. Of these rituals, Chunchuhyangsa was considered the most important.

The rituals took two days to complete, including the preparation process that was done the day before. The preparations usually involved preparing the foods and utensils to be used, deciding who the officiants will be, and writing the chukmun, or a document read at the beginning of a ritual to call upon the spirits of the enshrined persons. On the second day, the participants would wake up at dawn to prepare physical and mentally for the ritual. After everyone dressed in the required attire, they would gather at the shrine. The officiants would then conduct each step of the ritual as written on a document called “holgi,” which was read aloud.

Learning

In early Joseon, the educational system—made up of hyanggyo, or provincial academies, and the sabu hakdang and Seonggyungwan, the highest state-operated institution of learning—was focused on state-operated institutions. The hyanggyo, attended by the sons of prominent families solely to prepare for the civil service exam, were lacking in terms of character development, as were the sabu hakdang, roughly equivalent to today’s middle and high schools. Seonggyungwan concentrated on cultivating bureaucrats well-learned in Confucianism to strengthen and maintain dynastic rule.

The seowon was different. Rather than focusing on preparations for the civil service exam, which was the main gateway to success in the Joseon dynasty, the seowon devoted itself to education on the elements of human nature based on a Neo-Confucian theoretical framework. Seowon students learned, on a daily basis, the values that they must have in order to live honorably. They were turned into true literati through an intensive process that developed both academic knowledge and strength of character.

Education at a seowon was based on two types of books: books on Neo-Confucianism and books written by the seowon’s enshrined individuals. Because of this, the curriculum of each seowon was unique to it. For example, Dosanseowon focused on the writings of Yi Hwang on his famous “heart theory” and universe theory, while Donamseowon concentrated on Kim Jang-saeng’s theory on rituals. Surviving records, including regulations on learning, curricula, assessments, and learning rituals, offer valuable insights into how education was done at the seowon.

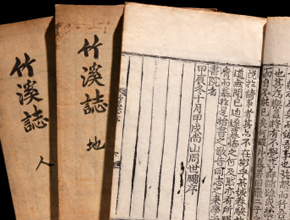

Today, most seowon still have many woodblocks and collections of writings by reputable individuals. These woodblocks and books contributed significantly to the proliferation of academic knowledge during a time when books were owned by only a small part of the population. Seowon students engaged not only in “book learning” but also often engaged in debates with one another late into the night on Neo-Confucian theories.

The spaces in a seowon that were used for teaching and learning were the Ganghakdang and the student dormitories: Dongjae and Seojae. The Ganghakdang, which was the largest building and usually located at the center of the seowon, was restricted to students except for class time. There was a wide daecheongmaru, or wooden floor, in the center that was used as a classroom. There was one small room to the right and left of the daecheongmaru, which were used as what we would call today the seowon director’s office and teachers’ room/lounge.

The seowon was different. Rather than focusing on preparations for the civil service exam, which was the main gateway to success in the Joseon dynasty, the seowon devoted itself to education on the elements of human nature based on a Neo-Confucian theoretical framework. Seowon students learned, on a daily basis, the values that they must have in order to live honorably. They were turned into true literati through an intensive process that developed both academic knowledge and strength of character.

Education at a seowon was based on two types of books: books on Neo-Confucianism and books written by the seowon’s enshrined individuals. Because of this, the curriculum of each seowon was unique to it. For example, Dosanseowon focused on the writings of Yi Hwang on his famous “heart theory” and universe theory, while Donamseowon concentrated on Kim Jang-saeng’s theory on rituals. Surviving records, including regulations on learning, curricula, assessments, and learning rituals, offer valuable insights into how education was done at the seowon.

Today, most seowon still have many woodblocks and collections of writings by reputable individuals. These woodblocks and books contributed significantly to the proliferation of academic knowledge during a time when books were owned by only a small part of the population. Seowon students engaged not only in “book learning” but also often engaged in debates with one another late into the night on Neo-Confucian theories.

The spaces in a seowon that were used for teaching and learning were the Ganghakdang and the student dormitories: Dongjae and Seojae. The Ganghakdang, which was the largest building and usually located at the center of the seowon, was restricted to students except for class time. There was a wide daecheongmaru, or wooden floor, in the center that was used as a classroom. There was one small room to the right and left of the daecheongmaru, which were used as what we would call today the seowon director’s office and teachers’ room/lounge.

Interaction

When people needed a break from the rigorous study program, they would set down their brushes and books for a short while to sit together in the seowon’s natural surroundings.

While composing poems and painting landscapes on the daecheongmaru, where there was usually a pleasant breeze, people recognized that nature is the best teacher. This was all done at the pavilion, a building in premodern Korea that was used for centuries as a place for relaxation.

The pavilion was a space to set aside the stress of the seowon schedule and refresh one’s mental energies amid nature.

The pavilion was also the “fanciest” building in the seowon, which is made up of simple, unadorned buildings. In this case, “fancy” is a very relative term: pavilions were not elaborately embellished, but effort was nevertheless made to make them special. Every pillar of a pavilion was carefully crafted, with the natural texture of the materials left exposed without varnish. The best part of the pavilion was the way it blended seamlessly with its natural surroundings, which was made possible by the absence of doors and walls. The pavilion is a space that is not defined by the view of the “inside” from the “outside,” but by the view of the outside from the inside. Ultimately, the purpose was self-reflection while viewing nature from the pavilion.

The trees, rocks, stream water, mountains, wind, frost, snow, and rain encountered by the sarim from the pavilion were all subjects for academic reflection. People gathered to talk about nature and their lives, write poetry, and paint.

Interaction at a seowon involved not only those who lived there but also outsiders. Reputable Confucian scholars and bureaucrats from all over the country often gathered at seowon to socialize. Today’s surviving seowon bear many wooden signboards (hyeonpan) that reflect the depth of academic learning and moral uprightness of their visitors.

For the seowon, “interaction” was a synonym for “communication and harmonious coexistence” between humans and nature.

While composing poems and painting landscapes on the daecheongmaru, where there was usually a pleasant breeze, people recognized that nature is the best teacher. This was all done at the pavilion, a building in premodern Korea that was used for centuries as a place for relaxation.

The pavilion was a space to set aside the stress of the seowon schedule and refresh one’s mental energies amid nature.

The pavilion was also the “fanciest” building in the seowon, which is made up of simple, unadorned buildings. In this case, “fancy” is a very relative term: pavilions were not elaborately embellished, but effort was nevertheless made to make them special. Every pillar of a pavilion was carefully crafted, with the natural texture of the materials left exposed without varnish. The best part of the pavilion was the way it blended seamlessly with its natural surroundings, which was made possible by the absence of doors and walls. The pavilion is a space that is not defined by the view of the “inside” from the “outside,” but by the view of the outside from the inside. Ultimately, the purpose was self-reflection while viewing nature from the pavilion.

The trees, rocks, stream water, mountains, wind, frost, snow, and rain encountered by the sarim from the pavilion were all subjects for academic reflection. People gathered to talk about nature and their lives, write poetry, and paint.

Interaction at a seowon involved not only those who lived there but also outsiders. Reputable Confucian scholars and bureaucrats from all over the country often gathered at seowon to socialize. Today’s surviving seowon bear many wooden signboards (hyeonpan) that reflect the depth of academic learning and moral uprightness of their visitors.

For the seowon, “interaction” was a synonym for “communication and harmonious coexistence” between humans and nature.